Last week, a session of The Social project that brings together people from different professions who aim to learn new things took place in one of St. Petersburg's bars. The project was launched in Switzerland three years ago and now involves about 40,000 people in 12 countries. Its goal is de-virtualization of human communication via the concept of inclusiveness. The organizers invite people from different fields to participate in their meetups, so that the topics would not be limited to just professional interests only and the networking process would take place in a community that is interested in new ideas and trends of the future. At the recent session, Pavel Belov, Dean of Faculty of Physics and Engineering and Head of ITMO’s International Research Center for Nanophotonics and Metamaterials, gave an informal lecture in which he shared his opinions about modern science as seen from Russia.

Funding

Nowadays, it is not only governments but also companies that finance research projects. For one, many companies have their research centers with apt research teams. In such circumstances, science is undergoing particular changes, and is becoming more focused on practical tasks. Nevertheless, 90% of the world's science is still concentrated and generated at universities. In Russia, however, the situation is slightly different, as we have this long-standing tradition of concentrating most research at the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The image of a scientist

The new approach to science that sees it as some practice-oriented "knowledge production" brought significant changes to many of its aspects, the image of a scientist included. The new scientist is an effective manager, almost a entrepreneur, who can spend only five percent of their time on science, and the remaining 95 on the issues of management such as searching for personnel, fundraising, choosing a promising research field and such. The results they get largely depend on how well they perform these tasks.

In the past ten years, the attractiveness of science careers has increased a lot. In 2000s, the profession of a scientist was very unpopular, only a little less than that of a janitor. The image of a scientist was associated with being dirt poor. Nowadays, I assure you, those who know what's what drive expensive cars, live in good apartments and get European-level wages. Besides, they don't steal this money, but make it legally by providing the research results they've been funded for. Such a change occurred after the government made the decision to fund science by allocating grants. So now, we can say that Russia has taken up the European approach to science.

Science is global

Modern science is international. Pursuing science all by yourself is no longer efficient. Nowadays, research tasks are often being worked on by whole international teams. The skills and competencies necessary for a project are often taken from different places, for example, it may involve numerical techniques from Great Britain, equipment from Australia, ideas from Russia and so on. Such an approach to science differs greatly from the "iron curtain" that existed in Russian science during the Soviet era, when a scientist could only work at a particular institution on some particular project ordered by the government. For some, this change may be hard to get used to, but these are the realities of modern science. It doesn’t matter what exactly a particular research institution has, they just can't compete with the opportunities offered by the international scientific community.

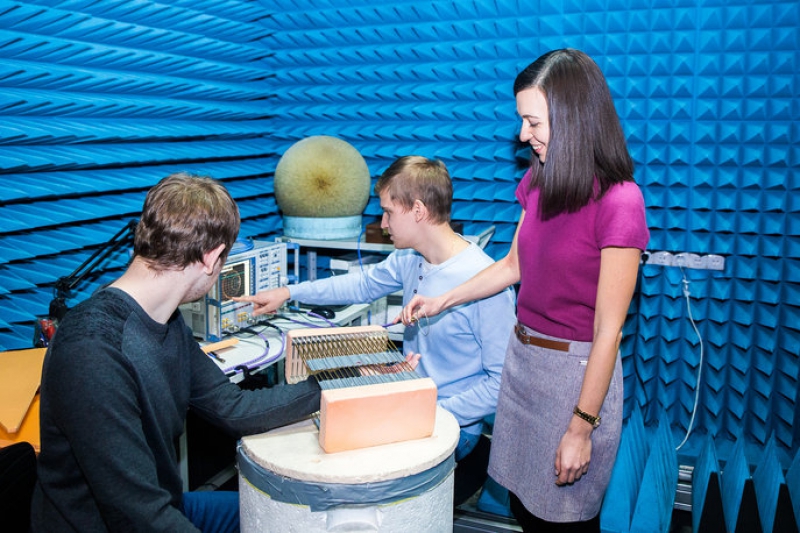

In our research center, for instance, we study magnetic resonance tomography. As no one manufactures MRI tomographs in Russia, working on our project implies collaborating with Dutch companies that manufacture them, Belgian colleagues who develop numerical techniques, Finns who manufacture magnets and the English who provide us with antennae. This way, research projects can involve people from all over the world.

Academic mobility

Many young scientists go abroad, but that's not what you’d call brain drain – it’s mobility. You can't get the necessary qualification while staying at one place only, be it in Russia, Great Britain or the USA. On different stages of your education (Bachelor's, Master's, PhD and so on), you have to go to different places and get different experience. In Finland, they even forbid staying to work at the same university for two years after you've had your thesis defence. The young scientist has to go to some other place, get the necessary experience, and only then they are allowed to return.

Science is made by the young

According to statistics, those who make breakthrough inventions mostly do it when they are from 30 to 40 years old, after which the probability of making an invention is very low. In other words, modern science is made by the young. I have a pupil who's studied in Russia, Europe and Australia, defended his PhD at 32 and is currently among Russia's most cited scientists.

Transferring scientific knowledge

You pursue science in order to create new knowledge, and this means that you also have to transfer it. Making inventions is just not enough, the system for transferring knowledge is also very important. In today’s Russia, the system with publications is messed up. Oftentimes, scientists don't understand the true purpose of publishing their results. Many believe that it's being done for the records, or some similar reason, but fail to understand that what's most important is that some other person would read their work, and read it where there's much demand for scientific content. You have to publish your work somewhere people would read it. It is also important to appear at conferences and see them as not an opportunity to visit new places, but an opportunity to communicate with colleagues from other countries, exchange information and establish contacts. Good research teams do that naturally. Information communicated at conferences is a very effective instrument, as it gets transferred faster, and is quick to affect research results all over the world. Another important activity is promoting science to the public. As of today, this format is being rapidly developed in Russia, though by the younger generation only.

Russian-speaking scientific community

Unfortunately, most Russians who pursue serious science left the country during the Perestroika and are now working in Israel, the USA, Europe and other places. About 80% of noteworthy Russian-speaking researchers are now located outside of the Russian Federation. This community is very effective, and in every research field, the top reports at every conference are made by people whose surnames are associated with the former Soviet Union. These people all know each other, they communicate at conferences and reside in different countries. Most live in the USA (which is now the leading country in terms of science), others in European Union, China and so on. As for the scientific community in Russia, its representatives fall under two categories: the older generation that survived through the Perestroika and the returnees, i.e. those who returned to Russia from other countries. Personally, I am a returnee: 10 years ago, it occurred to me that I could benefit from returning to Russia and continuing my work here.

Daria Sofina

Journalist

Vasilii Perov

Translator

Последние новости

-

-

Butterfly Effect: ITMO Researchers Create Colorful Perovskite Films for Optoelectronics

-

Scientific Show, Lectures, and Lab Tours: Recap of Physics Day 2025 at ITMO

-

ITMO-Developed Metasurface Makes Optical Chips 2x More Efficient

-

“Combing” Light: ITMO Researchers Find Reliable and Fast Way to Transmit Data in Space